SUMMARY

- Programmatic advertising, the automated buying and selling of digital ads based on demographic tracking and targeting, is the bedrock of the online economy, providing the majority of revenue for a large number of news websites and social media platforms.

- Post-2016, the censorship industry manufactured crises for brands by cherry-picking examples of ads next to extremist content.

- Online censors exploited these crises to insert themselves as middlemen in the programmatic advertising industry, advising brands on where they should advertise online.

- This allows the censorship industry to financially throttle disfavored websites, influence the policies of social media platforms, and discourage websites from catering to the “wrong” audiences.

A top priority of the censorship industry since 2016 has been extending its influence over programmatic advertising. But what is programmatic advertising, and why does it matter?

A simple explanation is offered by Steven Brill, co-founder of NewsGuard, one of the most influential private companies in the censorship industry. As Brill explains in the video below, programmatic advertising is less about advertising on particular websites, and more about advertising to particular people.

“Advertisers have found that because of programmatic advertising which basically is advertising that follows you, or a certain demographic that resembles you, it doesn’t care what it doesn’t care what website the ad is on – it cares about what you may be looking at. So brand name, highly reputable, advertisers have found that in their programmatic advertising they are ending up on fake news sites which undermines their credibility and really embarrasses them. So the way we’re going to help them solve that is we are going to license in effect a whitelist, which is all of our green sites.”

The digital era, with its combination of big-data powered technologies like social media and tracking cookies has enabled companies to build detailed profiles on their users based on their web browsing habits. Today, digital advertisers have a clear picture of our age, race, income level, geographical location, as well as our political affiliations. This allows advertisers to identify entire demographics of users and tailor ads to their preferences.

It also means that advertising is spread out across a multitude of websites, with complex algorithms determining the best ad placements for brands. These algorithms track potential audiences around the web at lightning speed, calculating what ads should be placed while webpages are loading. The goal is to put ads in front of the users most likely to click on them, wherever on the internet they happen to be at any given moment. This means that advertisers only have a vague idea which sites their ads will appear on.

The Programmatic Ads Censorship Playbook

In theory, this shouldn’t matter to advertisers, as long as their ads are reaching the desired audience and delivering a good return on investment. This was the case for many years before the election of Donald Trump in 2016.

After that election, everything changed: the censorship industry began to punish brands for their previously agnostic approach to the sites and pages their ads appeared on. Brands would have to factor a new consideration into their advertising strategy – the threat of negative media coverage and nonprofit-led pressure campaigns if they advertised in the wrong places.

The first major deployment of the tactic came in 2017, against YouTube. The mainstream media cherry-picked examples of ads appearing next to extremist videos to trigger an industry-wide panic that, according to some estimations, resulted in hundreds of millions of dollars in lost advertising revenue for the platform. As early as February 2017, just a month after Trump’s inauguration, the censorship industry fixated on programmatic advertising.

From The Times’ article credited with triggering the YouTube ad exodus:

Many of the companies said that they were unaware of and “deeply concerned” by their presence on the sites. They blamed programmatic advertising, a system using complex computer technology to buy digital adverts in the milliseconds that a webpage takes to load. Many agencies have their own programmatic divisions, which often apply mark-ups to digital commercials without the brands’ knowledge. Programmatic advertising enables agencies to track potential customers around the web and serve them adverts on whichever website they are browsing.

When the ad exodus hit YouTube, it was so unusual and widespread that it was dubbed “The Adpocalypse.” But the practice of deliberately triggering advertiser boycotts through activist pressure and negative media headlines was not a one-time event, confined to YouTube: it would be repeated again and again, becoming the censorship industry’s favorite weapon.

There was also the inevitable mission-creep, with justifications for ad boycotts quickly extending far beyond genuinely extremist content like the Jihadi YouTube videos featured in The Times’ article.

By 2020, posts from then-president Donald Trump threatening the use of force against violent rioters were considered grounds for a massive ad boycott against Facebook. And as recently as last summer, the censorship organization Check My Ads cited mainstream conservative media companies Breitbart News, The Daily Wire, and Steve Bannon’s War Room as examples of programmatic advertising gone wrong:

In 2021, Warby Parker learned that it was sponsoring Daily Wire, an outlet whose hosts openly promote harassment and bullying toward transgender people, and even floated the idea of their “eradication.” Warby Parker pulled their ads within hours, confirming that they were “working to actively stop these types of ads from being placed. We do not condone this.” In August 2022, Check My Ads found ads for household brands appearing during commercial breaks for War Room, the livestream show hosted by Steve Bannon. Bannon, whose on-air monologues included calls for the beheading of Dr. Fauci, was sponsored by advertisers including Procter & Gamble, Nissan, and Audi.

Check My Ads is led by Claire Atkin and Nandini Jammi, the latter of whom spearheaded efforts to defund conservative websites at the left-wing activist group Sleeping Giants, which exclusively targeted the advertisers of Fox News and conservative websites, including Breitbart News, the Daily Caller, and Revolver News. At Sleeping Giants, Jammi also pressured credit and debit card companies to cut off services to the political right.

Its board of directors includes Joan Donovan, who until recently led a disinfo lab – the Technology and Social Change project – at Harvard’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy. Donovan is known for labeling factually accurate news stories including the Hunter Biden laptop story as misinformation. From a report in Scheer Post, co-authored by Matt Taibbi:

It was announced that the center would be closed in 2024 on the spurious grounds that project lead Joan Donovan lacked sufficient academic credentials to run the initiative (what was spurious is that it took that long for this realization to come about). Donovan was already widely known for partisanship and getting things wrong, in particular repeatedly claiming the Hunter Biden laptop was not genuine. The Shorenstein Center birthed two other key “anti-disinformation” initiatives, the aforementioned First Draft and the Algorithmic Transparency Initiative. Cameron Hickey, ATI’s lead, is now CEO of the much larger National Congress on Citizenship. In this video, Joan Donavan sits alongside Richard Stengel, the first head of the Global Engagement Center, an agency housed in the State Department with a remit to “counter foreign state and non-state propaganda and disinformation efforts.” The closing of the Technology and Social Change Project is a minor victory in an otherwise exploding field.

The “Brand Safety” Industry

Having manufactured the problem, the censorship industry would now sell the solution. What began with media scare-stories about ads from prominent brands appearing next to Jihadi videos has become a fully-fledged business, with companies like NewsGuard selling services to blacklist and whitelist websites from receiving ads.

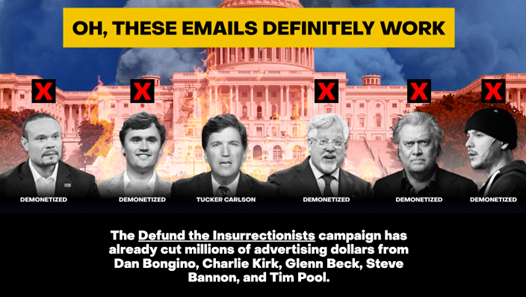

Meanwhile, partisan outfits like Check My Ads celebrate when disfavored news sources are denied advertising revenue. In one image produced by Check My Ads, the organization celebrates cutting “millions of advertising dollars” from Tim Pool, Steve Bannon, Glenn Beck, Charlie Kirk, and Dan Bongino.

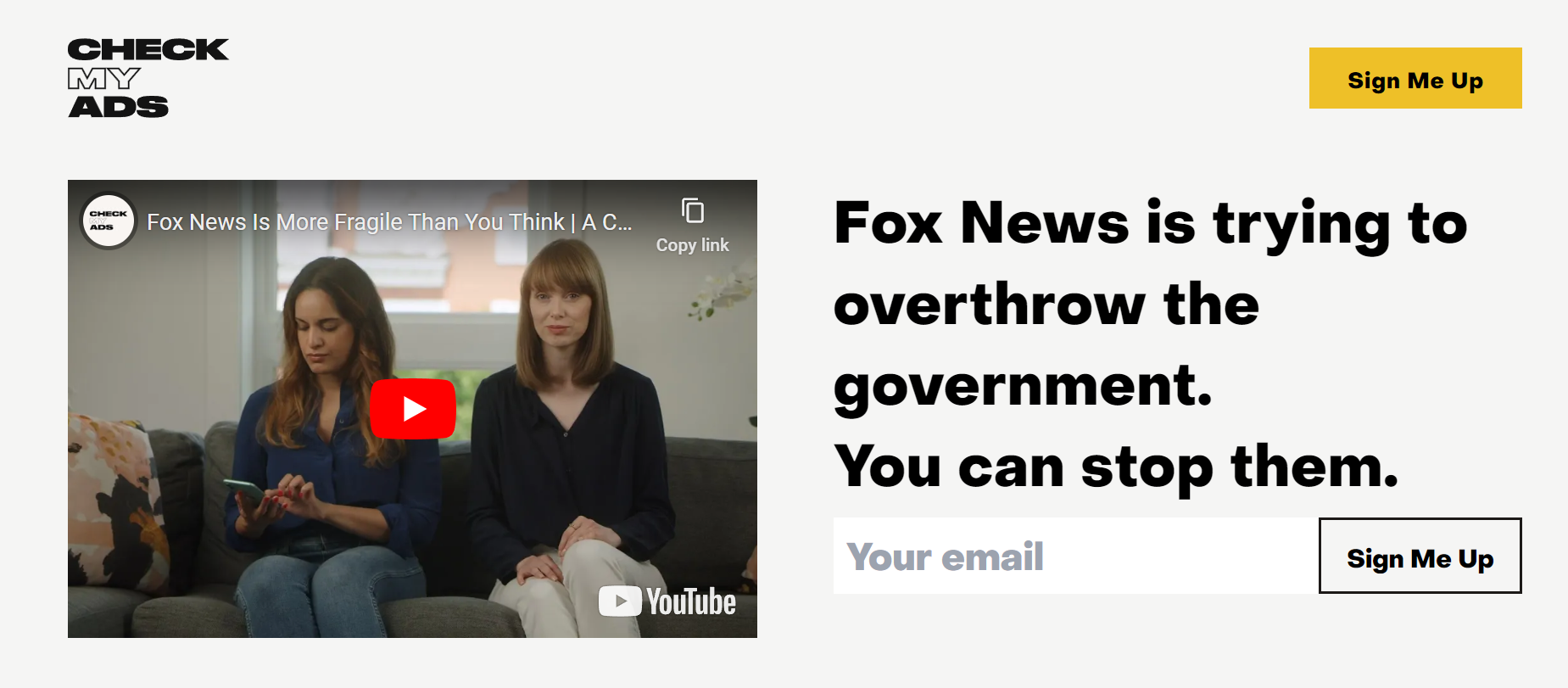

Another message from Check My Ads claims Fox News is “trying to overthrow the government.”

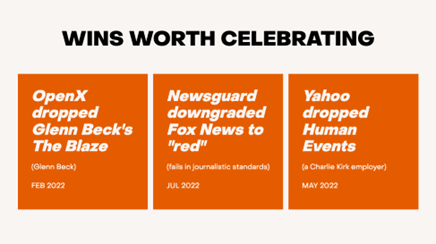

The organization also sees NewsGuard as an ally, celebrating it as a “win” that the company downgraded Fox News to a “red” rating for “failing in journalistic standards.”

The organization also sees NewsGuard as an ally, celebrating it as a “win” that the company downgraded Fox News to a “red” rating for “failing in journalistic standards.”

Unlike Check My Ads, NewsGuard doesn’t brand itself as a watchdog, but as a business. But its objective is the same: to control the outflow of advertising dollars to news websites, inserting itself as a trusted middleman in the programmatic ads industry, telling brands which websites are “safe” to advertise on and which are not. One of its flagship services are the “inclusion and exclusion lists” (another way of saying “blacklist” and “whitelist”) of websites, which it markets to top brands.

Many websites that have been given a score of 60 or less by NewsGuard, excluding them from its lowest “basic safety” level are some of the largest conservative, populist, and anti-establishment news sources on the web:

- Breitbart News, with a NewsGuard score of 49.5.

- Consortium News, with a NewsGuard of 47.5

- One America News, with a NewsGuard score of 25

- The Epoch Times, with a NewsGuard score of 17.5

- Newsmax, with a NewsGuard score of 15

- The Federalist, with a NewsGuard score of 12.5

- Revolver News, with a NewsGuard score of 7.5

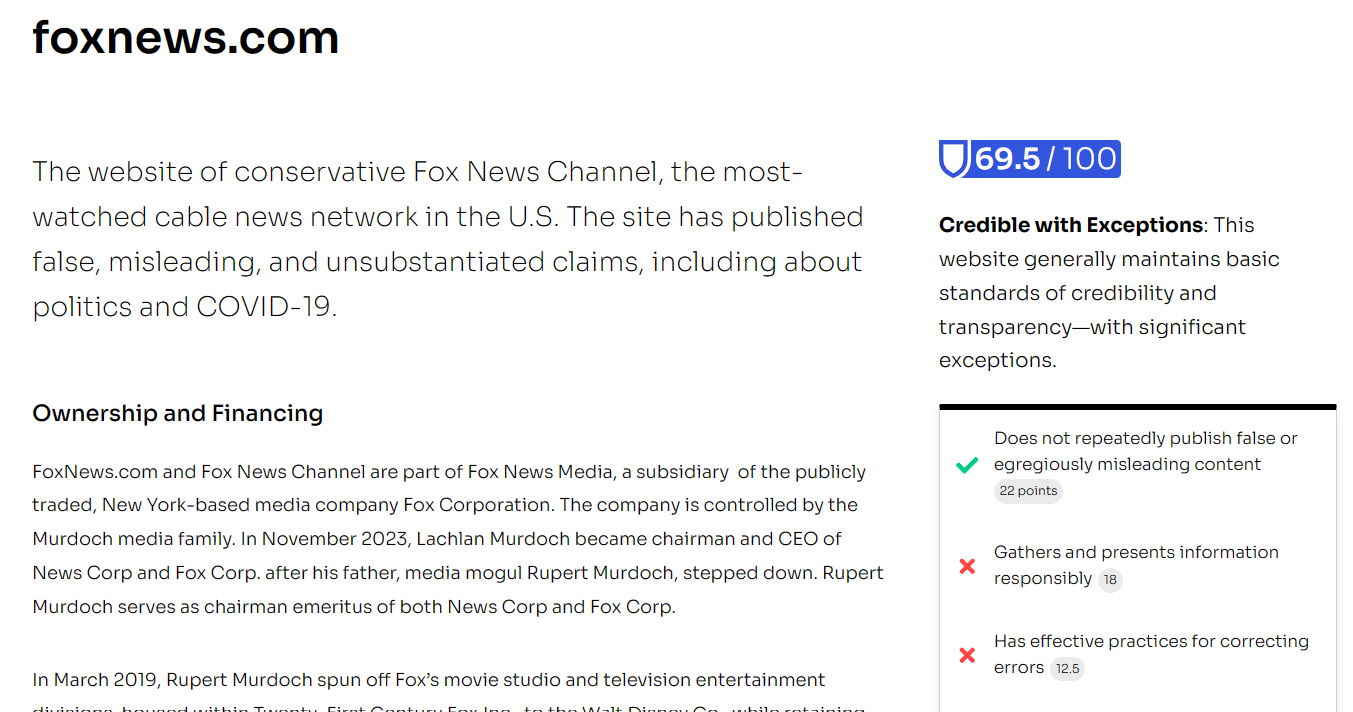

Fox News, with its NewsGuard score of 69.5, just scrapes into the “basic safety” umbrella. But it fails the next level, “high safety” as NewsGuard accuses it of failing to consistently “gather and present information responsibly.”

By threatening the programmatic ad revenue of media companies with its exclusion lists, NewsGuard hopes to influence the editorial policies of the entire online news ecosystem. The co-founder of the company, Steven Brill, is open about this goal, discussing it in a presentation shortly after NewsGuard’s founding:

We want people to game our system. We want a news site that gets dinged for not having a corrections policies to say, “hey I’m going to game their system, I’m going to put a corrections policy in, and I’m going to call them and tell them I’ve changed, I’ve got a corrections policy, now give me a check on that box.”

Of course, NewsGuard’s criteria for downranking news sites goes far beyond corrections policies. They include vague, arbitrary standards like the “responsible” presenting of information, the use of “deceptive” headlines, and the question of “handling the difference between news and opinion responsibly.” These are are all contestable terms, often in the eye of the beholder, and highly subject to the biases of whoever determines the rating. Yet NewsGuard hopes that brands will see them as the number-one authority on these matters, using them to decide where to advertise.

So, NewsGuard’s strategy is a twofold influence campaign: on the one hand, persuade brands and advertisers to see them as trusted middlemen in the programmatic advertising industry, guiding their ad dollars away from disfavored websites. On the other, persuade news websites to follow their lead – a goal no less ambitious than influencing the editorial policies of every news website on the internet. In the name of “safety,” brands that use NewsGuard are enabling the re-centralization of decentralized media – an unpopular mission for any brand associate itself with.

Economic Exclusion

The end result of the censorship industry’s campaign to control programmatic advertising is more than the financial throttling of particular websites. It also represents the economic exclusion of an entire swathe of the population. As Brill himself explains in the video above, the point of programmatic advertising is to identify demographics and their interests. By targeting anti-establishment websites with their negative ratings and pressure campaigns, the censorship industry is sending a message to brands, and to news websites, that some demographics are less valuable to cater to than others. The ultimate consequence is the economic exclusion.

Elon Musk has become the face of opposition to this censorship regime, after telling controversy-shy advertisers to “go f*** yourself” if they declined to advertise on X because of controversial content. As FFO explained at the end of 2023, this was more than an expression of frustration: it sent a signal to brands that they would have to choose between avoiding controversy and accessing X’s audience. Boycotting the platform and expecting policies to change would, according to Musk, no longer have an effect. If this message is internalized by major brands, it may result in fewer ad boycotts aimed at promoting censorship.