In 2022, the DHS awarded $750,000 under their Targeted Violence and Terrorism Prevention Program (TVTP) to the developers of a counter-disinformation video game for children in grades 6-9. The project, titled “Defenders Against Disinformation: Defeating Disinformation with Digital Gaming” used the funds to create a video game that pitted “superhero” governments, industry partners, and legacy media companies against disinformation.

The taxpayer funded project was created by the Wilson Center, a purportedly non-partisan nonprofit established by Congressional charter in 1968. Although the Wilson Center has contingency plans in place for lapses in federal funding, it still relies on Congressionally appropriated funds for one-third of its budget. It also enjoys a 30-year rent-free lease at the Ronald Reagan Building, a federal office building in Washington D.C.

In a statement to FFO, the Wilson Center acknowledged that the game received funding from DHS’s counter-terrorism program, and said the game will be “posted for all to see” on its website when complete. The Wilson Center said the game fits into its “scholarship driven” mission, without elaborating.

The Wilson Center’s statement:

“In April 2022, the Department of Homeland Security issued a funding opportunity aimed at examining violent extremism and how it could be “exacerbated by…misinformation [and] disinformation….” The Serious Game Initiative was approved for funding to create a “serious game” that could help build media literacy using several international case studies. When the game is finalized later this year, it will be posted on the Wilson Center website for all to see just like previous serious games that have been created which can be seen here. In other words, it will be 100% transparent and public, in line with our nonpartisan, scholarship driven mission.”

This taxpayer-funded institution’s video games project, part of the Wilson Center’s wider “Serious Games” initiative, is further evidence of government involvement in attempts to psychologically “inoculate” members of the public (in this case, schoolchildren) against alleged disinformation.

As a previous FFO report has described, “psychological inoculation” techniques under research by private companies like Google and censorship institutes at universities, aim to prejudice the public against certain narratives, arguments, and viewpoint by exposing them to deliberately weakened versions of them ahead of time. One leading researcher in the field described it as “preemptively injecting people with a severely weakened dose of fake news.”

In its DHS funding application, the Wilson Center referenced the research on “psychological inoculation” as informing its development:

“This program would build off of previous practices to combat disinformation. Studies have illustrated an effective prevention method for disinformation is to use media to “inoculate” key audiences against disinformation, such as through watching videos that identify common strategies for disinformation so that the audiences are aware of malign actor strategies (Lewandowsky & Yesilada, 2021) or playing games the pre-bunk players and make them more resilient in the face of disinformation (Basol et al., 2020). This line of research suggests that through exposure to disinformation, the audience will become more resilient in the face of disinformation.”

In a November 2022 report, FFO revealed how the State Department helped produce a video game called Cat Park to “inoculate” young people against populist news content. The FFO report also uncovered how Cat Park served as a sequel to Harmony Square, created by DHS’s Cybersecurity Infrastructure and Security Agency (CISA) – (the government agency most closely associated with domestic censorship of the 2020 elections) and the State Department.

Harvard’s pro-censorship publication, the Misinformation Review, touted Harmony Square as a game that effectively “inoculates’ against political misinformation” during elections.

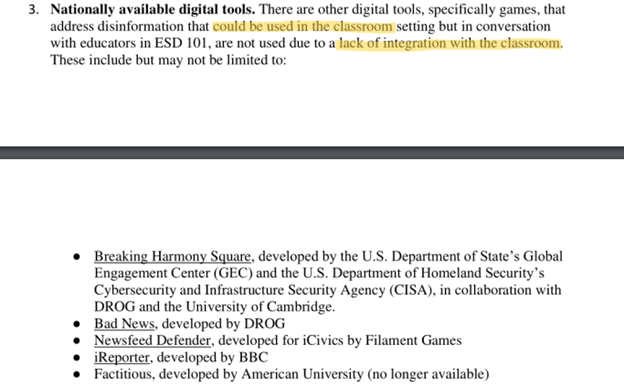

In its funding application, the Wilson Center wrote favorably about Harmony Square, but noted that it is “not used due to lack of integration with the classroom.” The Wilson Center said it would place greater emphasis on developing its games for use in American classrooms:

Additionally, the Wilson Center promised its games would show students not just how to recognize and reject disfavored information, but also how to “prevent and defeat” it.

To justify their framework to create this game, the Wilson Center boasted how they previously “created a workshop on Defeating Disinformation” for “Members of Parliament, Congressmen, and staff from the UK, Europe, and Brazil, and the US.” In this workshop, they used a “tabletop exercise (wargame)” that taught participants “not only how to identify disinformation, but how to work across stakeholder groups (i.e. media, industry, and government) to respond to disinformation — and significantly for prevention, the need to formulate both short-term and long-term collaborative plans of action.”

The Wilson Center concluded that they wanted to use the same strategy behind this “wargame exercise” for government officials into a format for middle and high schoolers.

Their proposed game would put players (i.e. middle and high schoolers) into the role of managing a team of superheroes. Superheroes in the game would represent the government, media, or industry — each one with unique “powers.” The game’s superhero manifestation of government has the power of “enacting national policy,” while “industry” superhero has the power of “flagging disinformation on platforms.”

From the game description:

Players managing their teams of superheroes will be given examples of “new emerging threats of disinformation.” The Wilson Center indicated that it will determine which specific examples of disinformation they use for the game based on interviews with “disinformation experts” within and outside of the center, meaning censorship industry professionals will determine which narratives are used for the game.

The disinformation “threats” that players must combat also vary. The Wilson Center explains that the game will allow players to marshal government-industry-media powers not just to target speech that is false or “harmful,” but also “fairly harmless offensive rhetoric.”

The Wilson Center also admits that an objective of the game is to get schoolchildren to agree that suppressing so-called disinformation is important. Whether a student “feel[s] there is more that can be done about disinformation” is one the ways the Wilson Center says it will measure the game’s efficacy.

The “Media Literacy” Expansion

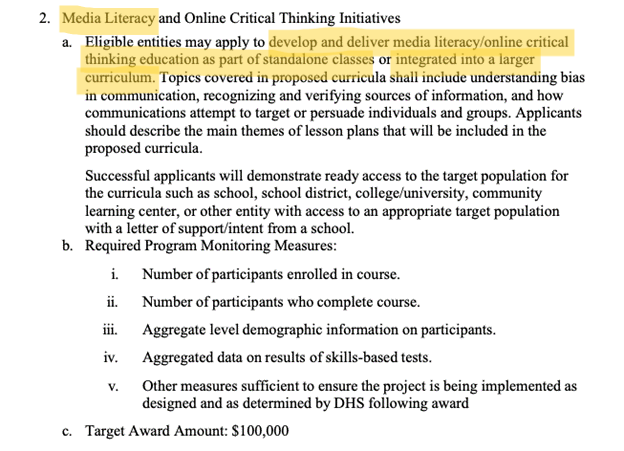

In its 2022 DHS Notice of Funding Opportunity for the TVTP grant program that funded the Wilson Center’s project, the DHS explicitly solicited funding for media literacy initiatives that could be integrated into education curriculum. The Wilson Center’s Defenders of Disinformation game grant is categorized under this funding track for “media literacy and online critical thinking initiatives.”

“Media literacy” is the idea of psychologically training citizens not to trust or access certain types of establishment-disfavored media. FFO previously reported on media literacy efforts in the U.S., particularly its manifestation within the education system. NewsGuard, which offers a media literacy service, has partnered with the 1.7 million strong American Federation of Teachers as a client, and states such as California are passing laws mandating the study of “media literacy” in schools in an effort to pre-bias children against certain information sources. Washington State, where the Defenders of Disinformation game is set to be used in classrooms, is one of the leading states in passing legislation to develop “media literacy” education.

The Wilson Center’s Defenders of Disinformation is developed for classrooms in the North East Washington Education Service District 101 (ESD 101), which included over 28,414 students in their target population from 6th to 9th grade at the time of the grant application. Their plan included consulting with educators to ensure the game is tailored specifically for the public education setting.

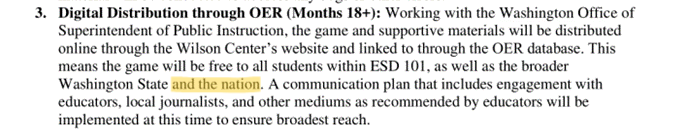

While the original project will integrate and evaluate the game for students in grades 6-9 across school districts in Washington’s ESD 101, the Wilson Center indicated that the endgame of their project would be to distribute the game across both Washington State and the nation, free of charge.