SUMMARY

- The censorship industry is concerned by Latino voters’ growing sympathies for populism and Donald Trump.

- The National Conference on Citizenship (NCoC), a purportedly nonpartisan nonprofit established by a Congressional charter, launched the Algorithmic Transparency Institute (ATI), which pioneered efforts to monitor and censor Spanish online speech.

- ATI targets speech that has “ill effects,” regardless of its factual accuracy.

- An ATI-incubated project called the “Civic Listening Corps” encourages Americans to spy on each other, reporting cases of disfavored speech on an online database called Junkipedia.

- Organizations targeting Spanish speech for censorship hope to use this formula to infiltrate and monitor private messaging groups.

The government-backed censorship industry’s partisan objectives, in particular its concern with hindering the global populist movement epitomized by Donald Trump, has been extensively documented by FFO. A matter of growing concern for internet censors is the drift of Latino voters towards Trump and the Trump-dominated Republican party, which first became apparent during the 2020 election and continues to cause alarm in the media.

This report will shed light on the efforts to advance censorship in Latino communities. Through a censorship project called the Algorithmic Transparency Institute (ATI), and an intricate network consisting of a foreign-language speech flagging team, Latino-facing civil society organizations, and everyday Spanish-speakers in America, the censorship industry’s leading institutions were able to build a network dedicated to targeting online speech in the American Spanish-language community related to elections and COVID-19 vaccines.

The NCoC’s Algorithmic Transparency Institute

The Algorithmic Transparency Institute (ATI) is a censorship project housed within the National Conference on Citizenship (NCoC).

NCoC was chartered by congress in 1953, “to harness the patriotic energy and civic involvement surrounding World War II,” but in recent years the organization – one of the fewer than 100 nonprofits nationwide established directly by congress – has redirected its mission towards suppressing online speech. The ATI was launched by NCoC in 2020, and quickly became a pivotal player in the censorship industry. In particular, it promoted the concept of “civic listening” — encouraging American citizens to report each others’ online activities to the ATI’s censorship database.

Cameron Hickey, who previously led Harvard’s Shorenstein Center Information Disorder Lab, was selected to be the Director of ATI in 2020. Hickey seemingly was rewarded for his role in the censorship operation — in addition to directing the ATI, he now serves as the CEO of the entire NcOC.

Harvard has 4 (!!) different centers all involved in social media censorship operations.

– Belfer Center

– Berkman Klein Center

– Shorenstein Center

– Kennedy Center https://t.co/rFVvhpMKQL pic.twitter.com/fwZz66TczW— Mike Benz (@MikeBenzCyber) September 6, 2023

Hickey’s contributions to the censorship industry include three initiatives incubated within ATI in 2020, all of which have the targeting of Spanish-language online speech as a key component:

- Junkipedia: This “digital public infrastructure for civic listening” is a Frankenstein-like censorship tech tool . It gives the ability for censors to flag and collect insights on speech across and narratives across any platform online, even in closed-messaging communities popular amongst the Spanish-language community such as WhatsApp. This database gave analysts from the Election Integrity Partnership, the nexus of the government’s censorship laundering operations, the ability to analyze speech across different platforms and foreign-language communities that had been flagged for censorship.

- Ethnic Media Fellowship: The Ethnic Media Fellowship pilot program recruited foreign-language journalists to flag content for censorship. Nine fellows representing different foreign-language communities were selected for the effort to report “problematic content” within their respective community into Junkipedia. One of the reasons for their recruitment was their access to private messaging groups, because disinformation “spreads in closed and encrypted communications platforms that are nearly impossible to explore by anyone but the members of their respective communities.” Their reporting allowed censors visibility into popular narratives amongst different ethnic communities and the ability to skulk around in their private messaging groups.

- Civic Listening Corps: This is the grassroots movement of the censorship industry. The Civic Listening Corps is a program that trains volunteers to monitor content and encouraged to police the speech of fellow citizens, flagging any “problematic content” they find for censorship. They sign up for speech monitoring shifts and report content directly into Junkipedia.

The Ethnic Media Fellowship and Junkipedia became instrumental in the censorship industry’s efforts to to target Spanish-language speech online. ATI recruited foreign-language journalists to carry out the work of the project, which was ostensibly started with the sole focus of “track[ing] problematic content related to the 2020 U.S. census.”

Ensuring an accurate census count became only a small part of the EMF’s mission. As the year progressed, the Ethnic Media fellows became almost exclusively entrenched in flagging online speech relating to the most politically sensitive events of the time: the 2020 elections, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the Black Lives Matter movement.

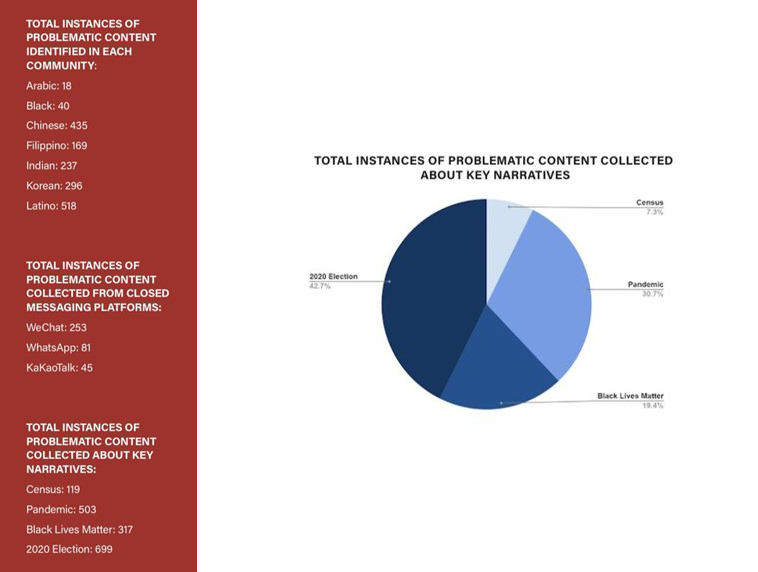

In 2020, only 7.3% of “problematic content” EMF collected had to do with the Census. 42.7% of all the speech flagged for censorship was about the 2020 elections, 30.7% was about the pandemic, and 19.4% was about the Black Lives Matter protests. While Ethnic Media Fellows with native proficiency in multiple different languages were selected for the project to monitor 7 different communities, 30% of the total instances of problematic content reported about “key narratives” were identified within the Latino community.

There is no clear guidance on boundaries on the speech that fellows chose to flag. Their own report reveals that the “problematic content” they reported was not merely speech that is false or purposefully put out to cause harm. They admit to targeting factually accurate, truthful speech for censorship:

We use the umbrella term “problematic content” as it encompasses several kinds of content: mis- and disinformation, hate speech, conspiracies, and other content that may not be factually incorrect, but can have ill effects nonetheless.

Even private speech, in closed text messaging platforms such as WhatsApp, a highly popular platform for Spanish-speakers, was being reported to the censors. As seen above, 81 “total instances of “problematic content” were collected from WhatsApp by the Ethnic Media fellows.

According to their report, two out of the nine fellows expressed frustration that they were not able to easily access WhatsApp. They explained that “WhatsApp groups are often created on familial or fraternal bases and it may not be possible for a journalist or researcher to gain access to such groups if they don’t already have close ties to the groups’ members,” meaning that in order to report content from this platform into Junkipedia, Spanish-language censors needed to have some sort of personal connection within their ethnic community to infiltrate a WhatsApp group.

2020 Election Censorship: The Election Integrity Partnership

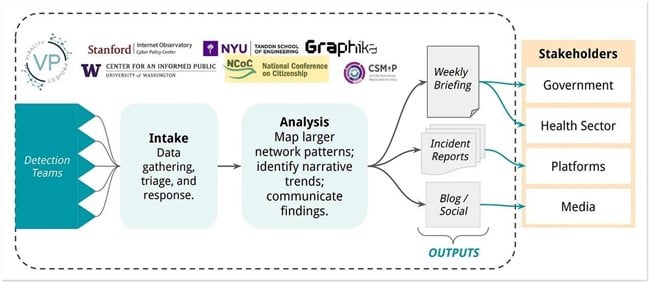

According to the censors own reports and the Junkipedia website itself, ATI’s censorship tech tool was used by the DHS-born Election Integrity Partnership to censor the 2020 elections, and afterwards by the same coalition rebranded as the Virality Project, to censor COVID-19 discussion.

From Junkipedia:

Junkipedia already has over 100 organizations using the platform to share or investigate narratives and instances of misinformation. We work with several existing coalitions focused on this problem to ensure that information flows across platforms and gets where it needs to go. We partner with the Stanford Internet Observatory for both their Election Integrity Partnership, and the Virality Project to enable their analysts to monitor across networks, and receive inputs from our network of civil rights non-profits and ethnic media reporters monitoring non-english content in underserved communities.

In its post-2020 election censorship report, EIP also confirmed the role of ATI and the Junkipedia tool in the election censorship effort. They said that the tool, along with ATI’s network of journalists, “provid[ed] visibility into more geographies and communities” (i.e. foreign-language communities) and aided “detection by EIP analysts” to censor speech:

Another noteworthy civil society partner was the National Conference on Citizenship, specifically their Junkipedia team. Junkipedia is a research tool created by the Algorithmic Transparency Institute, a project of the National Conference on Citizenship, to collect false and misleading social media content. The tool served dual purposes: first, it connected EIP to content surfaced through its own network of journalists and reporters, providing visibility into more geographies and communities; and second, it facilitated research and detection by EIP analysts, who were able to use Junkipedia’s list feature to track account activity on TikTok and YouTube.

EIP analysts directly accessed Junkipedia to monitor Spanish-language disinformation relating to the 2020 elections. While a plethora of civil society organizations and volunteer members of the Civic Listening Corps were reporting content into the censorship database, a large portion of speech surfaced directly to EIP censors came from the team of 9 Ethnic Media Fellows at ATI. The fellows accounted for a quarter of all speech submitted to Junkipedia in 2020.

Insights about Spanish-language narratives relating to the elections from the ATI’s Ethnic Media Fellowship correlates directly to what the EIP had reported in their findings from the effort to censor the 2020 elections. For example, ATI presented a concern with the likening of Biden to socialism driving away Latino voters from voting democratic.

From the 2020 ATI Ethnic Media Disinformation Fellowship Report:

“Content or general narratives may resonate with a specific community. Though messages linking the Democratic party and President Joe Biden to socialism were a common attack line during the 2020 campaign, the narrative that Biden and the Democrats were the same as Nicolás Maduro and Fidel Castro was specific to Latino communities.”

EIP dedicated an entire section of their report to “Spanish-Language Misinformation.” In this section, the censors concluded that fact-checking efforts targeting Spanish speakers in the United States must take into account “narratives [that] connected Biden to socialism, which may have been intended to discourage Latino voters who fled the socialist regimes in Venezuela, Cuba, and Nicaragua from voting Democratic.” EIP additionally suggests that more “effective fact-checks” should be used against Spanish-language speakers online.

“Culturally significant messages were sometimes added to the misinformation, complicating the fact-checking process. For Spanish-language users, this content usually took the form of religious commentary denouncing socialism and the left, which appeals to Latino audience members who come from religious, often Catholic, backgrounds and/or who fled a socialist regime in their birth country. For Chinese-language users, this took the form of alleged collusion with the Chinese government or the Communist Party. Effective fact-checks were notably lacking for both of these communities: improvements to this process should not merely translate the fact-checking content into the correct language, but also take these cultural aspects into account.”

This part of the report appears to take issue with Latino voters’ skepticism of socialism. It suggests that fact-checkers need to take “cultural aspects into account,” like the lived experiences of Latino Americans who fled socialism, to counter narratives that drew parallels between Democrats in the U.S. and left-wing socialists abroad.

Covid-19 Censorship: The Virality Project

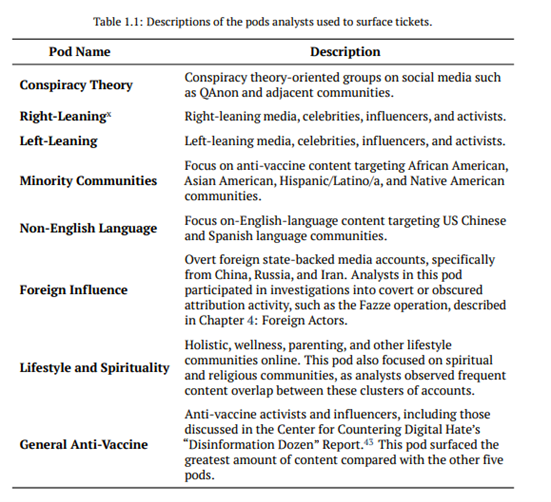

After the election, The Virality Project paid close attention to countering Spanish-language skepticism of Covid vaccines online. The censors were divided into 8 different “pods,” or teams of analysts focusing on surfacing tickets of flagged speech relating to a particular category of interest. Those tickets were sent directly to tech platforms so that the speech could be censored.

One team of analysts was dedicated to anti-vaccine content in minority communities including Hispanics/Latinos, and another pod was dedicated to non-English language speech of Spanish-speakers and Chinese communities.

From the Virality Project’s Final Report:

In addition to the 4 organizations involved in the EIP — the Stanford Internet Observatory, University of Washington’s Center for an Informed Public, the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensics Research Lab, and Graphika — the NCoC’s ATI became an official partner of the Virality Project.

In a Virality Project weekly briefing dated June 16 – June 22, 2021, the censors’ own meeting notes describe how the “Foreign Language Fellows at NCoC” were monitoring changes in the spread of “anti-vaccine content in both Spanish and Chinese.” As shown above, these weekly briefings were sent directly to stakeholders in the government.

“Foreign Language Fellows at NCOC following foreign language content have found that the volume of anti-vaccine content in both Spanish and Chinese has slowed in recent weeks. While content continues to spread, our partners have recorded significantly less novel material.”

In one weekly briefing, the Virality Project censors lamented an interview of Dr. Anthony Fauci conducted by Mexican actor Eugenio Derbez, complaining that Derbez used “anti-vaccination framed questions.” They concluded that “despite intentions for positive public messaging among Spanish speakers, Derbez’s questions amplified vaccine hesitancy and had an overall negative effect on public discourse.”

The Virality Project took issue with Derbez identifying himself as a “vaccine skeptic” early in the interview:

“Derbez, who at the beginning of the interview admitted he is a ‘vaccine skeptic,’ asked Fauci several questions popular in the anti-vaccine community, enquiring about pharmaceutical companies’ liability, the likelihood of long term negative effects, if injecting humans with mRNA is an experiment, why some bishops have told Catholics to avoid certain vaccines and the possibility of vaccine mandates.”

This follows the general shift of the censorship industry’s focus after the 2020 election, as it attempted to maintain relevance in the COVID years.

Tiplines and Snitching: The Role of External Latino Civil Society Organizations in the Censorship Effort

One of the challenges the ATI sought to solve was something that has been faced by every speech-monitoring organization in history, from the NKVD to the CCP: how do you monitor the speech of citizens, when so much of it takes place in private?

The ATI solved this in much the same way as those other organizations: convince members of local communities to snitch on each other. The ATI achieved this through a Junkipedia feature that allowed any partner organization to create its own tipline to report “problematic content” to online censors.

While ATI offers this feature to any organization partnered with them and even provides a step by step guide on creating and managing tiplines, the creation of tiplines is most prominently used amongst Latino-facing organizations. One example is the National Association of Latino Elected Officials (NALEO).

After Virality Project analysts began using Junkipedia for censorship of Spanish-language speech online, NALEO partnered up with ATI to roll out an initiative called “Juntos Podemos,” entirely dedicated to getting Latinos to report their community members to online censors. In the context of COVID-19, the initiative advised Latinos to report anyone who blamed “powerful individuals, companies, countries, or political parties” for the pandemic.

That means that if a Spanish-speaker in the U.S. shared their opinion that China was to blame for the pandemic, other Spanish-speakers were being encouraged to report that speech to an online censorship database — even if it took place in a private WhatsApp group.

In addition to NALEO’s effort to get Spanish-speakers to report their peers for disfavored COVID-19 opinions, they also encouraged Latinos to contribute to the ATI’s Civic Listening Corps, and to the Virality Project, encouraging Latinos to report “problematic content” to these organizations on a volunteer basis. Spanish-speakers were being recruited as a grassroots censorship effort, to root out “problematic content” in their communities.

Besides NALEO, several other Latino-facing organizations started displaying Junkipedia tiplines to encourage viewers to report the speech of their peers during the Virality Project censorship effort and afterwards (see here and here for examples). Since their involvement with the EIP/Virality Project, it has not been uncommon for Cameron Hickey himself to appear on webinars (like here) to train members of such partner organizations and the Latino community on how to report online speech to his Junkipedia contraption.

The Future of Spanish Language Censorship

Defiende La Verdad is NALEO’s newest campaign to establish a Spanish-language online snitching network through the Junkipedia tipline system. The campaign follows the same principle as Juntos Podemos, only rebranded to train and encourage the Latino community to report election related speech of their peers rather than focusing on content related to COVID-19.

According to the Poynter Institute’s Politifact, Defiende La Verdad, through tiplines managed by ATI’s Junkipedia, encourages the reporting of speech on closed messaging apps popular amongst Spanish speakers like WhatsApp to censorship organizations. If you are a Spanish-speaker in the United States, your peers are being encouraged to surface your text messages to censorship organizations.

“The National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials, which operates in Austin, Houston and nationwide, launched Defiende La Verdad, a webinar program that trains Latino community members on how to spot misinformation and how to report it on Junkipedia, an online tool used to collect and analyze misinformation so it can be countered by journalists, civic organizations and researchers. Misinformation across many platforms, including messaging apps like WhatsApp and Telegram, can be reported.”

Monitoring the Latino community’s WhatsApp activity is something that the government-partnered censors hoped to examine more closely during the 2020 elections. The EIP bemoaned that their ability to “consistently monitor WhatsApp was limited,” but that they were able to gain some insight into the platform’s use within the Latino community, presumably from the Ethnic Media Fellows.

“Our ability to consistently monitor WhatsApp was limited, but some have reported that it was used to send mass political, and even threatening, messages to Spanish-language speakers.”

Other censorship organizations, including Media Matters for America, are also reportedly ramping up efforts to monitor WhatsApp because of its popularity amongst populist Latinos. They explain that the reason they want to target private encrypted texting chats is because it’s difficult to censor these platforms.

Liz Lebron serves as research manager at Latino Anti-Disinformation Lab co-run by Voto Latino, a nationwide organization, and Media Matters for America, a nonprofit that seeks to counter conservative misinformation.

Lebron said one way to tackle encrypted misinformation is to remove misinformation from platforms such as Facebook and Instagram before it jumps to encrypted platforms. Such efforts are underway, for example, by Meta, which owns WhatsApp, Facebook and Instagram. But, Lebron said, more resources can be devoted to combating misinformation in languages other than English and collecting better data on what posts are being fact-checked and tagged.

“When it goes into an encrypted app, it’s really difficult to track it. That’s why it’s so important for the platforms that are public-facing to take down bad content. Because people are taking that content and moving it to private encrypted chats and spreading it there to their relatives and friends,” Lebron said. “One way to cut down on that practice is to remove that misinfo from the public-facing platforms as best as we can, as fast as we can, as much as we can.”

Media Matters, NALEO, and Common Cause have also banded together to create the Spanish-Language Disinformation Coalition (SLDC), overseen by the National Hispanic Media Coalition. In October 2022, the coalition wrote a letter to the CEO’s of Facebook, Twitter, Youtube, TikTok, Instagram, and Snapchat to demand they enact and enforce more stringent content moderation policies and dedicate more resources to flagging and removing Spanish-language content online ahead of the 2022 midterm elections.

During the 2022 midterms, SLDC partner organization Common Cause operated a Spanish-language tipline. They reported having 4,600 examples of “problematic content” submitted to their tiplines during the 2022 midterms and Georgia runoff election. After tips were submitted, their “disinformation analyst” directly contacted platforms to remove the speech.

They additionally shared that the Civic Listening Corps and Junkipedia had been “instrumental to [their] success”, and that many of the volunteer monitors currently at ATI learned to monitor online speech through Common Cause’s 2022 election counter-disinfo operation.

The SLDC includes partisan outfits like Upshift Strategies, a political communications firm whose clients include the DNC and the National Abortion Rights Action League. Another member of the coalition is the Omidyar Network, one of the most notorious venture capitalists of the censorship industry and a key funder of ATI’s Junkipedia and Ethnic Media Project.

In 2022, the Omidyar Network pledged $10 million on research into moderating encrypted text messaging platforms such as WhatsApp, and funding censorship tech tools to monitor private messages.

Omidyar Responsible Tech Overview Sample Portfolio:

As the 2024 elections approach, a vast apparatus now stands ready to advance censorship in Spanish-speaking communities. If Latino support for populist candidates and causes grows, we can expect this apparatus to be deployed, with all signals pointing to a greater emphasis on the monitoring and censoring of encrypted private messaging groups.