- Brazil’s election court announced it may nullify election winners who spread online ‘misinformation.’

- Hundreds of censorship professionals have been hired to read text message chats in Telegram and WhatsApp for ‘misinformation’ to report for apps to ban.

- Financing for censorship of Brazilian citizens’ text messages is coming from USAID, the State Department, and the National Endowment for Democracy.

Brazil’s upcoming October Presidential election is a high-stakes test for just how far the censorship industry can push its powers to manage online speech.

In Brazil, private texts to family and friends are fast becoming as targeted by “counter disinformation” techniques as public-facing posts on social media. This escalation of fact-checker interventions and sharing limits on texts has been introduced through new speech constraints on popular encrypted chat apps, WhatsApp and Telegram. These developments are being funded by millions in US tax dollars earmarked for foreign aid.

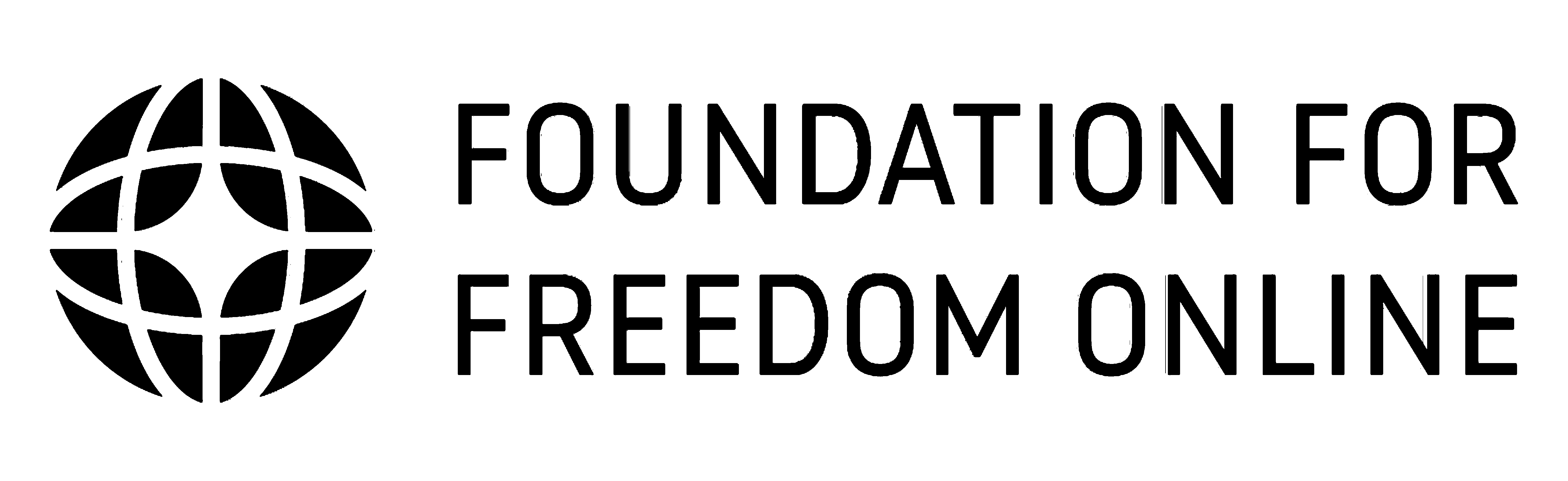

Before delving into the specifics, let us begin with a history of how the stage was set. WhatsApp and Telegram have been in the censorship industry’s crosshairs since late 2018, when free speech on texting apps was blamed for allowing then-candidate Jair Bolsonaro to become president of Brazil. This statement is hardly an exaggeration; to show how brazenly such sentiments were expressed at the time, below is a headline round-up from 2018-2019, citing the BBC, the Council on Foreign Relations, The Guardian, Fast Company, HuffPost, Reuters, The New York Times, Quartz, and the world’s largest fact-checker network, Poynter:

The seeds for 2022’s budding system of text message censorship were planted in the aftermath of Bolsonaro’s electoral victory. In June 2019, an #ElectionWatch panel of the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research (DFR) Lab’s disinformation global summit in London specifically targeted Brazilian populist voter sentiment expressed over text messages. In May 2018, Facebook designated the Atlantic Council an official partner in “countering disinformation” worldwide.

To illustrate what “disinformation” means to the #ElectionWatch panel, we will first show a scene from a preceding panel at that same event. Below, you will see two “disinformation” experts, Ben Nimmo (now team leader of Global Threat Intelligence at Facebook) and Andy Carvin, train a roomful of vetted international journalists on how to spot “disinformation” in tweets by then-President Donald Trump and in ads promoting Brexit. Senior journalists were encouraged to hold up placards reading “Bullsh*t” as Trump tweets and Brexit slogans played across the screen:

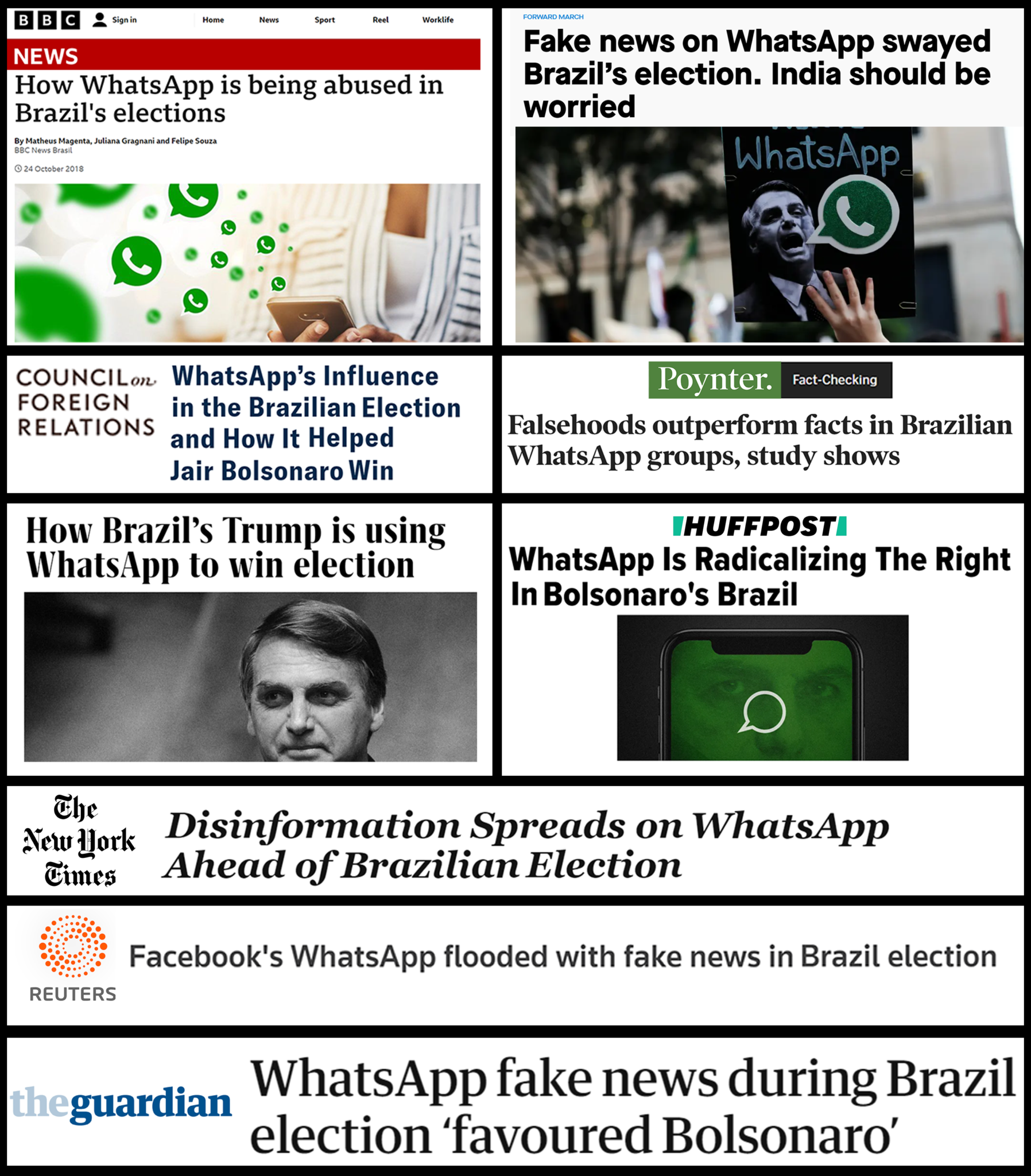

If this is a difficult video for American audiences to stomach, here’s another shocker: you paid for it. The Atlantic Council receives US taxpayer funding from the State Department, USAID, the National Endowment for Democracy, the Defense Department, the US Marines, the US Air Force, the US Navy, and numerous other federal agencies detailed below. That means the same electorate who democratically elected Donald Trump as President in 2016 also paid a NATO think tank to train journalists to muzzle Trump’s social media reach ahead of the 2020 election cycle:

After the censorship training session highlighted above, a subsequent panel from that June 2019 Atlantic Council summit discussed how to coordinate digital speech bans in response to what were considered two undesirable electoral outcomes in 2018: the rise of Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, and the consolidation of voter support for Narendra Modi in India.

Speaking in this first clip below is Fergus Bell. Bell’s “disinformation” pedigree is that he created a global media network to coordinate social media censorship in target countries all over the world through an alliance of privileged fact-checkers and vetted mainstream media journalists. Note how in the clip below, immediately after introducing the list of countries in which he has done “disinformation” election work, Bell pivots immediately to flagging “the danger of family WhatsApp groups” in India, because people in India tend to trust their own family members over credentialed fact-checkers:

The panel then went on to say that the Brazilian norm of trusting local family and friends over distant or discredited institutions created “a big problem” for fact-checkers in policing disinformation. Telegram and WhatsApp, therefore, presented a “danger to democracy” by allowing citizens to speak freely with one another, circumventing official guidance and trafficking in narratives disfavored by designated institutions:

Fergus Bell, the moderator of the censorship coordination discussion, then polled the room of prominent fact-checkers and vetted mainstream media journalists, and noted their common acknowledgment that direct messaging apps and local familial trust norms posed problems for all of them:

Note how, as early as the summer of 2019, the Atlantic Council’s US-taxpayer funded censorship coordinators had been targeting private text messaging apps precisely because of Brazilian and Indian cultural norms of strong trust in family, which supposedly undermined faith in institutions. Family trust was stamped by digital speech police as a threat to democracy.

Beyond their implicit quest to break the bonds of local trust, censorship insiders’ partisan bias in their Brazil operations have been even more explicit. The below May 2021 clip is from yet another US-taxpayer funded disinformation event, in which US taxpayer-supported Brazilian professor Marco Ruediger gave a presentation calling for a ban on the “international movement to exchange ideas” between pro-Bolsonaro groups in Brazil and pro-Trump groups in the US:

As noted above, both this event and its speaker, Prof. Ruediger, are US taxpayer-supported. The host of the disinfo event is the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (“International IDEA”), which is funded by USAID and the National Democratic Institute (“NDI”), both of which derive their funding from annual government allocations made by the US Congress:

The featured speaker in the video above, Prof. Ruediger, is a founding advisory board member of the Design 4 Democracy Coalition (“D4D”), which is also taxpayer-funded by the NDI and its sister group, the International Republican Institute (“IRI”). The NDI and IRI are notable in that they form the two explicitly partisan branches — representing the Democrat and Republican parties respectively — of the National Endowment for Democracy (“NED”).

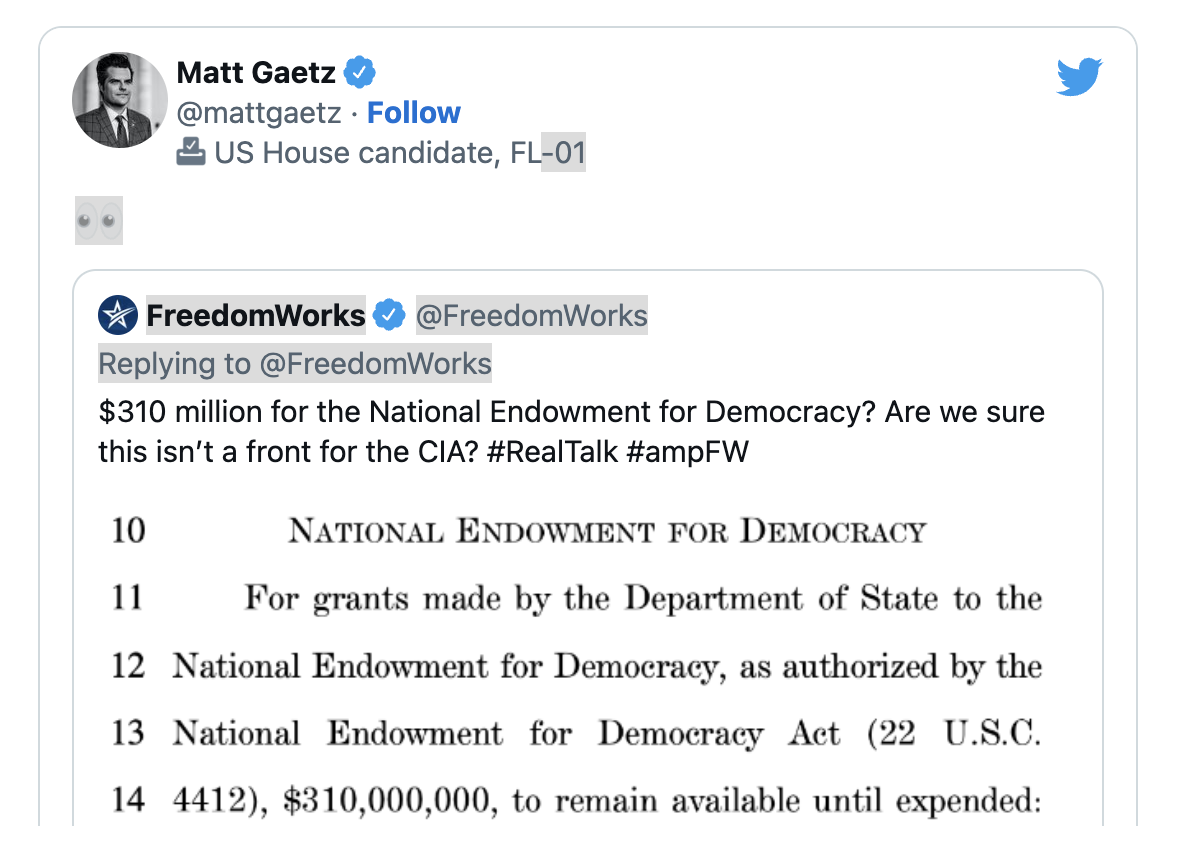

The NED has accrued considerable notoriety over the years, since its founding in 1983, as a semi-covert facilitator of US-backed coups of foreign governments. A 1991 Washington Post article about the NED entitled “The New World Of Spyless Coups” described NED as a publicly deniable, privatized branch of the CIA. NED co-founder Allen Weinstein told the Post: “A lot of what we do today was done covertly 25 years ago by the CIA.”

Per the FY2023 proposed budget for the US State Department, the NED is set to receive $310 million in taxpayer funds next year.

FFO expresses no opinion on the merits or pros and cons of NED’s mission or operations. Rather, we are identifying an Internet censorship concern. Given NED’s US taxpayer funding, and its nexus position within the operational networks of US foreign policy, NED’s hard pivot (begun in 2018) into coordinating global Internet censorship practices is especially disconcerting.

Last year, US taxpayers, through USAID, funded a NED operations manual for coordinating digital speech crackdowns around the world in the name of “countering disinformation”. That blueprint is available at https://counteringdisinformation.org/. The below clip, ominously tone-deaf in its eerie cheerfulness, is from a jointly USAID and NED-produced promotional video (via the Consortium for Elections and Political Process Strengthening, or “CEPPS”) debuting their joint Internet censorship guide:

Just how much of next year’s $310 million in taxpayer funds will NED be spending on Internet censorship? The amount is certain to be substantial. The NED and USAID-funded “counter-disinformation” guide and video above feature a video introduction by IRI President Daniel Twining (IRI being the Republican branch of NED’s organizational structure). Twining’s own Twitter feed suggests virtually no nation on earth will be spared NED’s social media “disinformation” interventions in the years ahead. On Twitter alone, Twining singles out operations needed or underway in Mongolia, Moldova, Madagascar, Malaysia, Latvia, Lithuania, Ecuador, Armenia, Ghana, Georgia, Malaysia, Nicaragua, Nigeria, and Tanzania:

For Americans, it is critical to internalize that this NED funding of “counter-disinformation” is not just targeting speech in foreign nations, where at least an argument exists that influencing the global information ecosystem serves a national interest. As illustrated in the video above, US domestic groups expressing a populist, anti-establishment political bent are every bit as much in NED’s crosshairs as their foreign counterparts in Brazil. This is the US foreign policy establishment putting a thumb on the press of domestic American democracy functions.

Target 2022: Brazil

With the above as background, let us return to new censorship developments in Brazil ahead of its October election.

Last month, Brazil’s election court crossed a world-first Rubicon by suggesting it may nullify election winners who spread online “disinformation”. The court’s declaration was aimed squarely at incumbent president, Jair Bolsonaro, who international fact-checkers like the Atlantic Council have accused of spreading false information. Bolsonaro’s speech crime was saying Brazil’s electronic voting system may be prone to fraud, in remarks similar to those made by US President Trump in 2020.

Brazil’s new “disinformation rule-of-law intervention” is a novel tool in the censorship industry’s toolkit. It comes on the heels of the Brazilian Supreme Court banning and criminalizing the use of popular private messaging app Telegram earlier this year. Brazil’s high court threatened $20,000 fines on any Brazilian citizen who tried to access Telegram via a VPN to circumvent the Brazilian Internet service provider ban. This heavy-handed fine was significantly more punitive than even the Chinese Communist Party’s response to citizens using a VPN to circumvent the Great Firewall, where fines are typically under $150.

The Telegram ban was made under the thin pretext that the app had become a vector for pro-Bolsonaro “disinformation”. Bolsonaro supporters only turned to Telegram in the first place because so many hundreds of thousands of Brazilians had been banned or hindered from speaking freely on Facebook or Twitter after the global social media crackdowns on “right-wing populist” movements during the early years of mass censorship infrastructure established in 2017-2018.

Telegram’s messaging services are end-to-end encrypted, making it difficult for outside censors to turn virality nobs down on domestic narratives shared among citizens using traditional AI techniques, including algorithmic downranking and mass account bans, as had become the norm on social media by late 2018, when Brazil’s last election took place.

Following Brazil’s ban on Telegram this March, the New York Times sought to minimize the enormity of the ban with its headline, “Brazil Lifts Its Ban on Telegram After Two Days.” The fine print is that the ban was not lifted because Brazil’s high court realized it was wrong to ban neutral text messages platforms; the ban was lifted because Telegram quickly bent the knee and deleted the very pro-Bolsonaro content and prominent pro-Bolsonaro user accounts that global fact-checkers accused of spreading “misinformation.” Telegram further agreed to label direct messages shared by users “false information”, implement mass content bans, and have Telegram personnel trawl popular group chats for any hints of disseminating officially deemed falsehoods.

In other words, under threat from regulators, Telegram saved its own skin in Brazil by giving international fact-checker syndicates and allied politicians the same power to censor and control direct messaging apps that they acquired in 2017-2018 over social media platforms.

Why the focus on Telegram in 2022? Because Facebook-owned WhatsApp already bent the knee to the censorship industry in 2019, after the initial onslaught of international pressure to apply speech constraints to private message groups in Brazil. Just two and half weeks after Bolsonaro was sworn in as President in January 2019, WhatsApp banned the ability to forward private messages to more than five people. This limit was applied explicitly in the name of adding “friction” to potential “misinformation” on WhatsApp by not allowing any particular message to achieve viral spread. For virality, messages among family and friends would have to travel across social media, where the fact-checkers and full-time censors would be waiting for them.

Many further self-censorship actions were subsequently taken by WhatsApp as the texting app became increasingly coopted by censorship industry stakeholders. WhatsApps’s pliant, surrendering responses came amid increasing regulatory threats to its owner, Facebook, who faced substantial pressure in 2019 from legislators seeking to break up its data monopolies.

Telegram had been much less cooperative, and was therefore much more censorship-proof, which is how it ended up the prime target of the censorship industry ahead of the 2022 Brazil election.

The Bigger Picture

What is happening now in Brazil is a microcosm of a subtle but devious development. A whole-of-society push is underway to redefine what “democracy” means. Through this new definition of “democracy”, censorship can be justified on a mass scale to pick favorites in electoral outcomes around the world by labeling “threats to democracy” as a censorable offense.

The trick being pulled is a definitional one: “democracy”, as a term of art used by stakeholders in the censorship industry, no longer refers to the consensus of individuals, but rather the consensus of “institutions”. This subtle re-definition inverts the centuries-old premise undergirding democracy’s legitimacy: that democracies govern “by the consent of the governed.”

This new definition of democracy — the rule by a consensus of institutions, rather than by a consensus of individuals — is now enforced through an increasingly ubiquitous definition of “disinformation” applied by fact-checking orgs, trust & safety teams, and their international government liaisons. As we see now in Brazil and around the world, “disinformation” means any incident, narrative or theory, expressed online, that has the effect of “undermining trust, faith or confidence in democratic institutions.”

Under this new definition – call it “neodemocracy”, if you will – groups who mobilize to challenge legacy institutions by pointing out their failings are, by definition, anti-democratic. And that definition provides a censorship predicate to ban their messaging and voices from the digital square. Indeed, “undermining trust in institutions” was precisely the predicate that NED-supported Prof. Ruediger, featured above, cited as the basis for increasing speech bans on populist groups in Brazil:

Note how at timestamp 1:02 in the video above, it’s stated that“It used to be that disinformation was a problem for elections. Now we’ve seen that, in reality, it stretches into any sensitive policy issues. Health, of course, but also migration and climate change.”This means any online narrative challenging any institutional consensus on any sensitive policy issue likely necessitates some sort of digital speech limitations being imposed on the electorate.

FFO will explore this dynamic much more in future commentary. Indeed, these very theoretical models are already being used by domestic censorship divisions housed within the US Department of Homeland Security. For much more on that, stay tuned.

Michael Benz is the Executive Director of the Foundation for Freedom Online. Previously, Mr. Benz served as Deputy Assistant Secretary for International Communications and Information Technology at the U.S. Department of State. Follow him on Twitter @FFO_Freedom.